Stewart Worland Smith was born on June 6, 1905, in Tomahawk, Wisconsin to Oscar W., owner of a wooden bucket factory, and Harriet Parker Smith, a librarian.

Stewart Worland Smith was born on June 6, 1905, in Tomahawk, Wisconsin to Oscar W., owner of a wooden bucket factory, and Harriet Parker Smith, a librarian.

In 1929, Smith earned a certificate in library science from the University of Wisconsin, where he had played on the football team, and following an injury, in the orchestra. His first library job was at the Milwaukee Public Library. The job was not particularly to his liking but he kept it since jobs were scarce during the Great Depression. He enrolled at Marquette University and earned a bachelor’s degree. With the degree, he was put in charge of the social science department of the Milwaukee Public Library.

Smith moved to Chicago where he earned a master’s degree in library science from the University of Chicago in 1940. He returned to the Milwaukee Public Library for a short time before moving on to be head librarian in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, and then Lincoln, Nebraska. He earned a reputation for creativity and not being hampered by the expectation that decisions be made based on tradition.

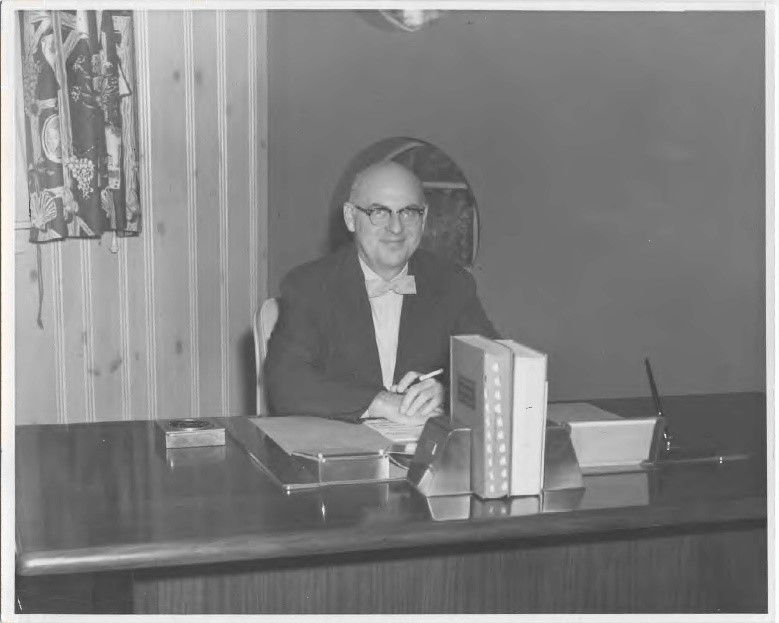

The St. Louis County Library was voted into existence in March of 1946 and Smith was hired as its first director. The library had no books, no staff, no buildings and no money since the first tax income was not due until the end of the year. His first office was a room in a Normandy school district building and that is where the initial planning for the creation of a major public library took place.

The St. Louis County Library was voted into existence in March of 1946 and Smith was hired as its first director. The library had no books, no staff, no buildings and no money since the first tax income was not due until the end of the year. His first office was a room in a Normandy school district building and that is where the initial planning for the creation of a major public library took place.

In 1946, St. Louis County was mostly rural. Some of the small towns in the county that were close to the City of St. Louis had their own libraries and were not interested in joining the County Library district. Smith had to demonstrate the value of library service to county residents who currently had no service. In the first two years of the library’s existence, there were two unsuccessful ballot measures to eliminate the library.

Smith’s early goal was to get books into the hands of people as quickly as possible. Rather than following established practices for cataloging and processing acquisitions, a simple record was made of title and author and a number was assigned to each item. Books were borrowed by patrons putting their name and address on the card designated for each book.

Another way that Smith got books into the hands of people in these early days was through interlibrary loan. He developed a partnership with the St. Louis City Library. County library staff would visit the main branch of the city library to search for, and borrow, items requested by county patrons.

Booketerias were also created in stores, banks, and other businesses throughout the district. Residents could borrow from a selection of 150 to 200 books by leaving an identification card with their name and address. The Booketerias were based on the honor system. They also included a book drop for returning items. When the library’s headquarters opened and bookmobiles began visiting neighborhoods and schools, the Booketerias were closed.

Booketerias were also created in stores, banks, and other businesses throughout the district. Residents could borrow from a selection of 150 to 200 books by leaving an identification card with their name and address. The Booketerias were based on the honor system. They also included a book drop for returning items. When the library’s headquarters opened and bookmobiles began visiting neighborhoods and schools, the Booketerias were closed.

Bookmobiles were a significant way that the new county library delivered services. They visited schools and neighborhoods. Schools allowed the library to install electrical outlets at the school so that generators would not be required. Smaller bookmobiles were used to provide service to one room schools spread across the western portion of the district. Some of the bookmobiles were equipped with loudspeakers, which were used to when driving through a neighborhood to announce their arrival, exact parking location, and the time of the visit. In densely populated communities with stores or shopping centers, a trailer that was towed to the site to provide service. During Smith’s tenure, the library’s bookmobiles were all built in-house by library staff (with the exception of the chassis).

When St. Louis County Library began constructing its first buildings, Smith rejected the prevailing style of library architecture and built light-filled and colorful interiors with curving bookcases, modern furnishings, and playful section labeling. Patrons could talk freely, smoke, and even bring their dogs to browse through books, records, and films while music played in the background.

Smith was the director of the St. Louis County Library from 1946 to 1968. Early in his tenure, he was active in the Missouri Library Association; Smith served as president from 1949 to 1950. Beginning in the late 1940’s, he was also a member of an informal group of around a dozen directors from other new county libraries throughout Missouri who met regularly on Sundays in Jefferson City with the Missouri State librarian to discuss library work. Smith was considered a key figure in the group.

During his time as director, Smith was instrumental in the passage of a few landmark pieces of legislation for Missouri public libraries. Smith successfully lobbied for the passage of a law which allowed political subdivisions to provide pension programs employees. It allowed St. Louis County Library establish its own retirement system. He also worked with other library directors to clarify the right of libraries to invest their own funds. Finally, Smith was responsible for the passage of the “Law of 1965”, which froze municipal libraries at their 1965 boundaries to prevent their encroachment into county libraries.

On January 7, 1975, Smith died of heart disease in Leesburg, Florida. He was survived by his wife, Elna Christine Smith, with whom he had two children, Stewart W. Smith, Jr., and Janet E. Smith Leslie. Stewart W. Smith, Jr., later served on the St. Louis County Library Board of Trustees.